05 – The Long Road to Digital

After we completed Utter in 1995 there was a short hiatus, primarily as lives had become busy with marriages and children, however, the next project was the start of a much longer journey to full digital production.

By 1995 I had joined Intel and was working on projects to move the internal computing systems away from a mainframe onto PC based architectures. Servers using Intel based architectures were evolving rapidly at this time which meant the hardware was frequently upgraded. A side effect of this was that, with the right permission, decommissioned hardware was passed onto staff. These servers were huge by modern standards, typically requiring a two-person lift but they were the most powerful computing available and, being primarily still a PC, could run Microsoft Windows along with standard PC peripherals.

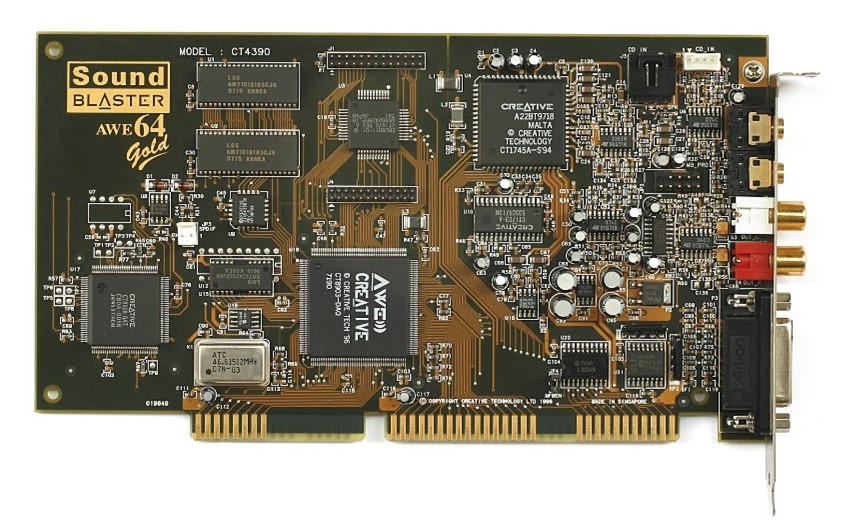

With the addition of a reasonable sound card, in our case a Sound Blaster AWE 64 Gold, we had the opportunity to start experimenting with digital music. Hard disk space at this point was measured in megabytes not gigabytes or terabytes but as we had a full server we could stack up several drives in a RAID array to improve things a bit, albeit making the server even heavier as hard drives were huge!

Home use digital music software was in its infancy with various companies developing formats and options with no clear leader or standard. The only thing that was standardised was MIDI – Musical Instrument Digital Interface – as that had been around since the early 1980s. Initially designed as a way for digital instruments such as synthesisers, drum machines and keyboards to communicate with each other, it does not send or manage actual digital music but purely sends instructions to tell digital instruments what to play. Once an interface for computers had been developed this created an ideal opportunity for computers to become the control centre and ‘sequencing’ moved to the heart of a lot of music production.

As MIDI just consisted of instructions for notes to play, its load on computer processing was manageable on the available hardware and so it became our entry point to a more digital approach. Software had been evolving for sequencing for a while and we messed around with several different products but our default moved towards Cakewalk by Twelve Tone Systems which had started life in 1987 as a Microsoft DOS program and evolved into one of the leading sequencers by 1994 with a version which ran on Windows.

As the Sound Blaster card had a built-in MIDI interface we could control certain instruments, record MIDI information from a keyboard and then, coupled with the music samples built into the sound card, we could play back in real time. It was a start but it gave us no way to record ‘real’ instruments or vocals, even though technically the sound card had the ability to do that.

The issues were in the computer hardware not having the processing capability or storage and the software being too immature. We tried numerous options and many of our planned precious recording sessions turned into engineering sessions as we battled hardware issues brought on by the server having rattled about in the back of a car for two hours as we transported it back and forth, or software problems with config and incompatibility.

Progress was slow, we had some content recorded on Freddie 2, we had MIDI based content and some limited direct audio recordings, Steve was composing new tracks far faster than we were recording them. Tush was still based in Spain and to make matters worse I started to travel back and forth to the US on a frequent basis, eventually relocating for a while in 1998.

For a period it looked hopeless and I felt we had tried to move too fast but two things brought back hope, the first was the release of Microsoft Windows 98 in 1998. Windows 95 had been a big step forward but audio at that point was still not a big factor in PC usage so it had many limitations. Windows 98 brought a number of improvements to both MIDI and digital audio processing in the operating system and opened up the path to far better music software.

At the same time Twelve Tone Systems evolved their Cakewalk product rapidly, particularly in moving it to become a DAW – Digital Audio Workstation – rather than just a sequencer. After Cakewalk 5 in 1994 we saw the arrival of Cakewalk Pro Audio 6 in 1997, followed by Pro Audio 7 in 1998, a short lived Pro Audio 8 in early 1999 and Pro Audio 9 in late 1999.

Across these versions we saw massive leaps forward in functionality which started to realise the potential of digital home recording. The issue was that with every new release we would have to go back and remix or at least check every recording because the processing and functionality was evolving fast and the output could sound completely different on different versions.

By 1999 we had an approach and sufficiently powerful hardware that we could record full audio from multiple instruments and mix it on the PC. What we could do in real-time in terms of mixing and adding effects was limited as the processing overhead was too high but with off line processing we could work around the limitation.

Most of the tracks on Accident & Emergency, as the project was eventually called, still had content digitised from Freddie 2, generally with vocals added directly in digital form and some other instruments directly recorded via the sound card too.

For one of the tracks, Oblivion, Steve hired a professional digital piano which had a MIDI interface. He played the track live and we recorded all the MIDI data into the computer, then using Cakewalk as a sequencer we edited any mistakes before playing back the MIDI data to the digital piano and taking its analogue output back into the sound card where it was digitised. The reason for this was that the audio sample quality of a professional digital piano in 1999 was far greater than what was available on a sound card and playing the track live first added MIDI data elements that would have been very hard to generate manually such as the key pressure and subtle fluctuations in timing.

Accident & Emergency was completed in late 2000, a couple of minutes shorter than Utter but with more tracks. Technically it shows as a transitional album with some tracks still exhibiting the wow and flutter from the underlying tape, just in digitised form, whereas other tracks are entirely digital. The move in technology also required a learning curve as new tools became available and our lack of experience with these tools shows in places, the result though is an album which is clearly a big step forward in audio compared to previous ones with some tracks holding up well against the test of time. Given the period over which it was written and recording there is quite a lot of variety on the album both in subject and style.

In 2022 I revisited the album and moved it to our current DAW, replacing some of the outdated plugins with modern equivalents before remastering. This digital remastered version is available on Spotify Accident & Emergency – Blue Powder (2000) and most other streaming platforms.